Few people in New York, it would be a safe assumption, have not experienced the pain of hunting for a roof–a room or an apartment.

Some of the lucky ones have sharper weapons and could open doors at a word, and some others, being less fortunate and poorly equipped, could go on knocking and knocking and knocking and still stay disappointed at the obstinately closed doors.

Yet the less fortunate ones need not to despair as all that, knowing it’s only natural to have a harder battle to wage when you only have such blunt spears in your hands.

And a line I came across earlier this week tells me “In the reproof of chance lies the true proof of men”. So, take courage, my friend, and hunt on! (Whatever it is that your are hunting for in your life.)

The Chinese word for “hunt” 找 zhǎo is about the hand and the weapon.

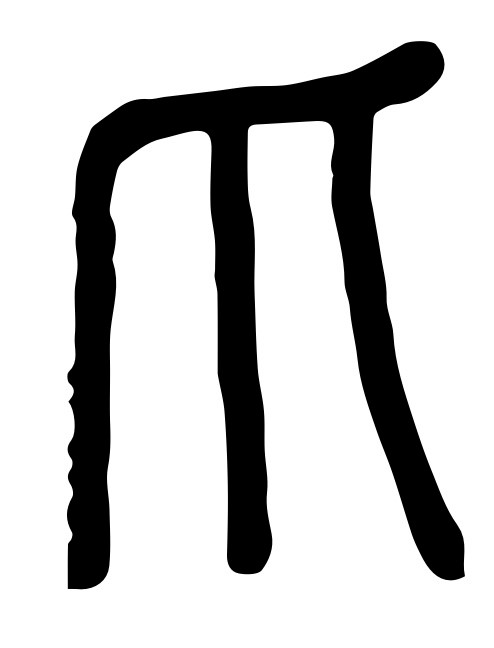

This character, 爪 zhuǎ,we still use today as only means animal’s hands: claws. And here is the original one that’s scratched on the bone:

And if you put a hand radical beside this claw and change the tone a bit, it becomes 抓 zhuā “to grab”, you could “grab a handful of peanuts” (抓一把花生米)or “grab(catch) a thief” (抓小偷).

Then, as the primeval man, very much like an animal, using his hands as claws to forage among the roots and grass and trees for food, he spots a hog and conceives a thought: what if I could kill it and eat it? Then the next question comes naturally: how to kill it? He stares and stares and stares at the branch of the tree in front of him and asks himself.

Here the weapon–the spear–comes in:

And it evolves:

戈 gē, though a character itself, now mostly is used as a radical. And you would not be surprised to find this radical in “war” 战 zhàn, or “opera or theatrical play” 戏 xì: think–if you have ever watched a Chinese opera–of the spear or sword the actors brandish about on the stage.

So from hunting with his claws, the primeval man updates his means and secures the spear and goes for the hog.

The claw 爪 is changed into a hand radical 扌and the weapon is put next to it, 找 zhǎo, he says, grabbing the spear, and he hunts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.