‘Wait’ is from Middle English: from Old Northern French waitier, of Germanic origin; related to wake. Early senses included ‘to watch with hostile intent, observe carefully, lie in wait for, plot against”.

The sense of being hostile while waiting is, perhaps, a familiar feeling with modern phone users: it certainly is interesting to observe one’s emotion while waiting for a reply of text messages, emails, or phone calls. And different people seem to have different code of how soon you should answer which only makes the matter of waiting more complicated.

One thing, as I read the explanation of this word, becomes certain: ‘wait’ is definitely not a passive action; it is related to wake, and it requires you to be watchfull and observe carefully.

The hostile feeling must come naturally in human emotions. Indeed it’s unpleasant to feel neglected and ignored, and we picture, as we wait for the answer, the other person is looking at their phones but chooses not to attend our messages: you are not important, the unanswered messages seem to say, and here hostile feelings rise up.

Yet it is all in your imagination. When you bond others to their phones, you bond yourself to yours. And really no one should be treated that way: I mean to be bonded with their phones at all times: there are countless other more pleasant ways to spend one’s time!

The past years must be a long wait for so many people on the planet (and the waiting is still on), and no one would argue that wait could be an active progress. And if you were lucky enough, through this long watches and observances, you must be coming out with a better knowledge of yourself.

As I looked up the Chinese word for ‘wait’, I came across all sorts of strange explanations: orderly bamboo slips, government houses, hunting and arrows, to serve and to observe, to stand……

等 děng, the modern word for ‘wait’ in Chinese, has the bamboo radical for its upper part, and the lower part 寺 sì, now means temple, in ancient times also means government houses. The character itself comes from the image of the bamboo slips ( We did write on bamboo before paper was invented and became accessible) put in an orderly manner. The meaning of the character then easily extended to ‘rank, grade, class, equal’: think rows and rows of piled up bamboo slips rolls.

The meaning “to wait” might come from the fact that ordinary people have to wait outside the government house to be admitted in. As both characters in this word meaning “to wait” have 寺 sì, government house, in them: 等待děngdài.

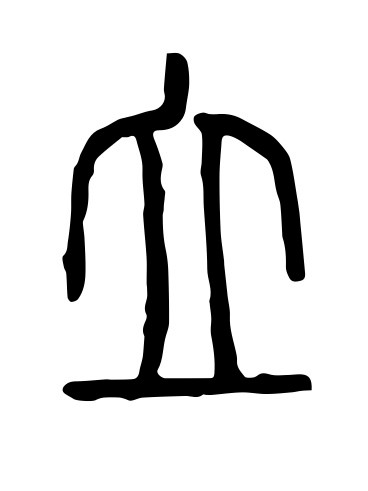

等候 děnghòu is another Chinese word for ‘wait’, and this 候 has all sorts of meanings: to reconnoitre, to observe, to forecast, to examine…and the character in ancient time has a different version(矦 hòu), it is related to a hunting event and consequently arrows:

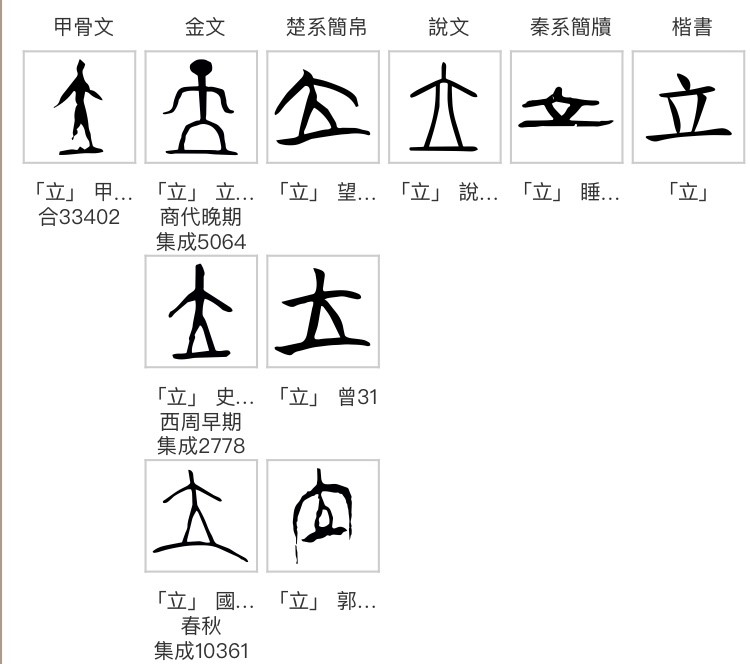

As I keep tracing the origins of this chinese character, as this or that delightful meaning comes up, I find that 等待, if you dug deep enough, comes also from 立 lì, to stand, to stop:

So wait, you can always wait it out if you waited long enough, and while you are waiting, why not think about what it actually is “to wait”?

You must be logged in to post a comment.