There is a distinguished air of Eastern Europe, that is, a sort of amiable working class genuineness. The sight of an unkempt fat man at the counter drinking a fat glass of beer, at lunch hour, at once gives an impression that life is not at all all misery. And the stout girl behind the counter—a mistress of a row of taps always inspires some sort of awe in me as if she somehow has escaped the common order of life—the stout girl asks to see our proof of entry.

So we sit down on the long wooden benches at the long wooden table. It’s a Polish restaurant on Greenpoint Avenue—later I was told there is a big Polish community in that area—and we are to have lunch in this place that I passed by one day and thought to myself: what is a Polish restaurant? Polish food, I was to learn over the course of lunch, very much like German, is mainly based on potatoes and sausages.

And I talked and talked, the little miseries that needed venting, the little happenings that were recent and new, and we laughed. And in this talking and laughing, and in the presence of a friend’s company, gloominess disperses and life’s grievaness smoothed over.

It must be later in life, for when you are young you tend to have such strong emotions and be so very serious about everything in life, it must be later in life that one learns the balance, the art of friendship.

君子之交淡如水 Jūnzǐ zhī jiāo dàn rúshuǐ, the friendship between gentlemen is as plain as water, is an ancient Chinese saying about the perfect balance: the friendship between gentleman stems from mutual understanding. In this understanding they are not demanding, coercive, jealous or clingy to each other, therefore in the eyes of ordinary people, it is as plain as water.

Yes, it is later in life, after experiences and mistakes, that we learn to demand little from others, we learn to allow their faults and laugh at our own.

朋友, péngyǒu, friends, is explained in this way: 同门曰朋,同志曰友 Tóngmén yuē péng, tóngzhì yuē yǒu, (entering) the same door (as learning from the same teacher, entering the same academy) is called 朋, (sharing) the same will (aspiration) is called 友.

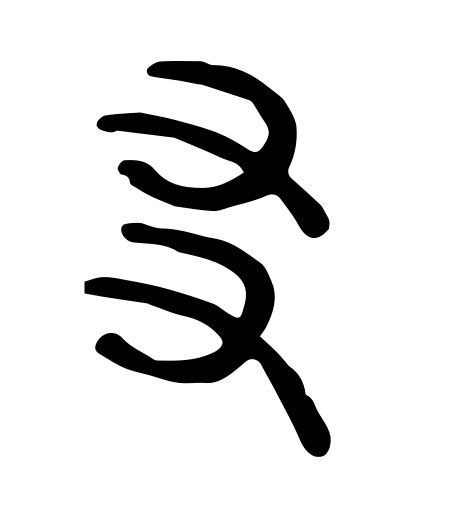

朋, though the modern interpretation could be two flesh (bodies), 月, leaning against each other, as we could daily see illustrated on any street such two bodies walking together, the origin is rather un-romantic: it’s an unit for currency: the amount of five coins stringed together:

友 has a more direct and close origin to the nature of friendship: a helping hand.

The irony of life, maybe, is that it is at the time that it’s difficult to make friends we learn the first steps of how to be a friend.

You must be logged in to post a comment.