It is an ambitious title, and with only the commonest knowledge in both, I could no more than attempt to just touch the very surface of it.

In China today, you could not see, as you would in Thailand, barefoot monks in orange or red robes walking in a line at dawn going around the neighborhood to accept almsgiving. Nor you could see, as in North India, holy temples dot the lower ranges of Himalayas, and in almost every household, there is a statue of Buddha, people there typically start their day by offering fresh flowers to Buddha and saying their morning prayers.

Once mother, when I touched upon this topic, said “I am a Buddhist myself”. I bluntly told her that by going to the temple once a year (often not even), burning some incense and asking Buddha to solve whatever problems she happens to have in life does not make her a Buddhist. ( We also call this “临时抱拂脚” in Chinese).

Yet, in one respect she is not wrong: merely by being a Chinese, she is a little bit of a Buddist. For it is on your tongue, in the language you speak, it is in the way you think, it is in your blood.

It’s said Buddhism came to China around 67A.D., so it has existed in China for nearly two thousand years, and with such a long history as that, it has time enough to weave and merge in every aspect of Chinese people’s daily life. And it has already, through these long years, ingrained in Chinese language and mind and has become a main part of China’s own culture.

Indeed, one of the Four Great Classical Novels(四大名著 sì dà míngzhù)–the four best-known Chinese classic works–Journey to the West(西游记 xīyóujì) is about a legendary pilgrimage made by five well-known characters: 唐僧, 孙悟空,猪八戒,沙和尚,白龙马 ( Monk Tang, Monkey King, Zhu bajie, Monk Sha, Dragon Prince), to the west region (西域 xīyù, modern day India) to obtain the Buddhist sacred text (佛经 fójīng).

It would be safe to say that no Chinese, children and adults alike, do not know these five persons, and for many a Chinese children, one of the pleasures in the long summer afternoon is to watch Journey to the West, and almost every Chinese little boy and little girl, has at one time or another, dreamed of being 孙悟空 the “Monkey King”.

It’s said there are about thirty-five thousand Chinese words come from Buddhism, and here are only a very few examples:

缘分 yuánfèn, lot or luck by which people are brought together, is a Buddhism concept deeply believed by Chinese, or Asian people.

慈悲 cíbēi, merciful, or to give others happiness, rescue others from suffering.

如意 rúyì, it’s originally a claw stick in ancient India–they still have it today–for scratching the back and relieving itching, coming to China, the word took up an auspicious meaning: satisfaction, good luck. 祝你万事如意, we still say it today “May all go well with you”.

善有善报,恶有恶报 Shàn yǒu shàn bào, è yǒu è bào, good deeds beget good deeds, bad deeds beget bad deeds, is a Buddhism concept, though in English, you also say “what goes around comes around”.

Also, some of the naming of the most common things are influenced by Buddhism. In China, especially in the north we also call our father 父亲 fùqīn, 爹 diē, this word is from some Buddism text when it was first introduced in China.

We call our fourth finger, the ringfinger 无名指 (Wúmíngzhǐ) no-name finger, is partially because in India they call this finger the same way.

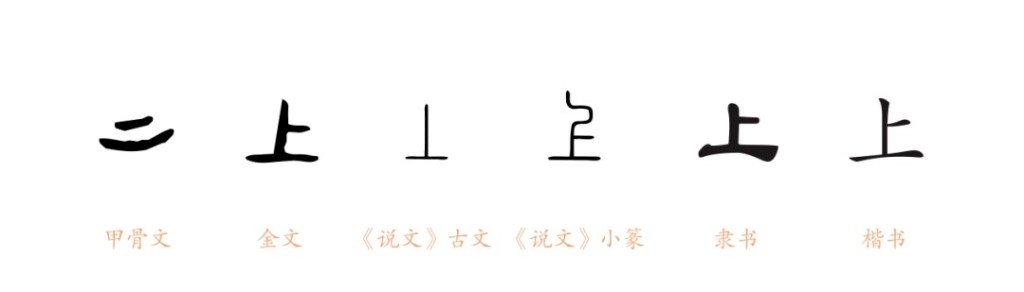

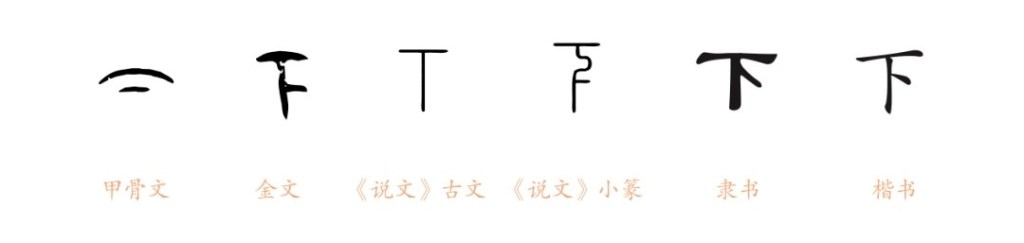

世界 Shìjiè, the world, in ancient China before the Buddhism was there, they call it “天下tiānxià” sky-under: under the sky; the world. 世 means three times lines: past, present, future, and 界 means the ten boundaries, or directions: east, south, west, north, southeast, southwest, northeast, northwest, up, down (东, 南, 西, 北, 东南,西南,东北,西北, 上, 下).

Even the word for wisdom in Chinese “智慧Zhìhuì” is from Buddhism.

Our mind is shaped by Buddhism: 境由心造 Jìng yóu xīn zào, or “circumstances/conditions are created by the heart”, or to translate is roughly, your attitude towards life determines how you live it, do you smell Buddhism in it?

It is in our poems: 出淤泥而不染 Chū yūní ér bù rǎn: out of the mud but not stained–it is a praise for the symbol of Buddhism: the lotus flower.

It is in our idioms: 盲人摸象 Mángrénmōxiàng, blind man touching the elephant, means only knowing part of a whole picture, 空中楼阁 Kōngzhōnglóugé castle in the air.

So when a Chinese, any Chinese, says that he is a Buddhist, he is not, actually, far wrong.

You must be logged in to post a comment.