You cannot sham an emotion in that situation, and we like it because we know the joys and tears are all true. It would be impossible to feign the passion or pain that overwhelms you when you win or lose a gold medal. True emotions move and are contagious too. I found myself laughing as the gold medalist jumps in triumph, and eyes wet when they–and you could tell from their tears the effort and the trails they must have gone through to finally stand on that podium–cry.

Also, it does you good to witness someone does a thing so well. It’s a moment to be proud of being a human, and you marvel at, once and again, the capacity of the human body. They do, literally, swim like a fish, run like a lion, or a leopard, or any other animals that could run so fast…… Admiration rises in your heart as you watch the perfection of their skill, the grace of their movement.

Homer himself when narrating Odysseus’s long journey home, takes a break and sets up a scene of sports competition. And as far as thousands of years back, we see, as we watch today from a screen, the same sights: there is bad luck, bike crushed, boat overturned, ankle twisted……there is much talent in youth (初生牛犊不怕虎chūshēng niúdú bùpà hǔ, literally, new-born calves fear not the tigers), smooth-faced teenagers are winning gold after gold with seeming ease and enviable confidence……there is pride, the raising of a proud fist, the up-pointing of index fingers(I am Number One!)……there is arrogance, the strutting around in the stadium……there is grace and friendship, the taking of a humble bow, the gesture of embracing your rival after winning the gold……

The English word “compete” is from Latin competere, in its late sense ‘strive or contend for (something)’, from com-‘together’+petere ‘aim at, seek’. And its noun “competition” is from late Latin competitio(n-)’rivalry’.

And the Chinese word for compete or competition “比赛 bǐsàiis” formed by two characters “比” and “赛”.

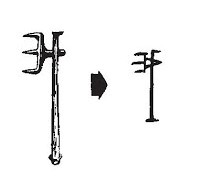

比 bǐ now mainly means “to compare”, interestingly, in the beginning it only refers to two very close people standing side by side, and it indicates, of course, “closeness”.

And one version of it is to put two very big people together:

Perhaps it’s human nature, when you put two people, or two things next to each other, you cannot help but to compare them, hence the modern sense of “compare and compete” derives from this same character that means “closeness” is not at all surprising.

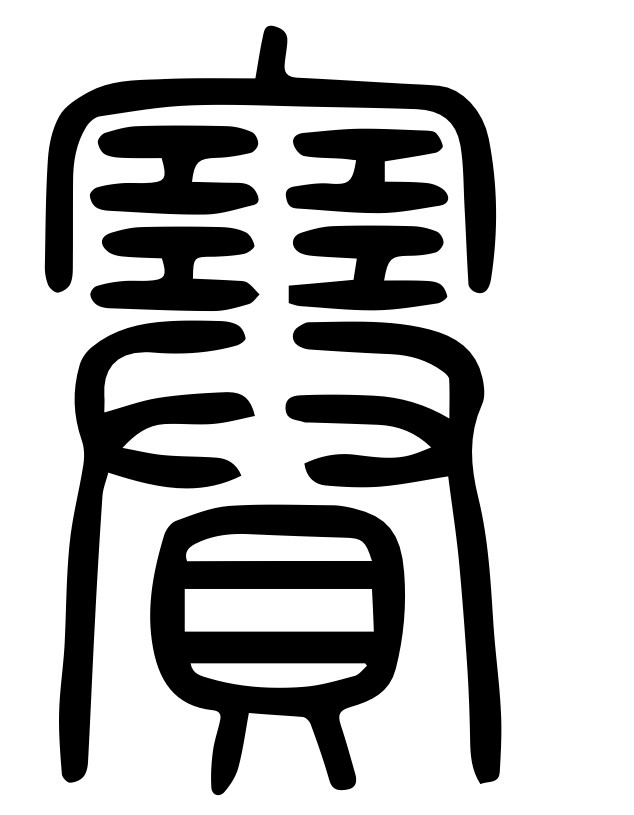

赛 sài , when I look at this character in the dictionary, finding out its original meaning, I feel that as different as we, humans, all are, from different backgrounds and of different races, there must be continuous echos since the beginning of time from all different cultures. Here this echo I heard is the ancient Chinese shouted out to the ancient Greece: 赛, its original meaning is “give offering of thanks to gods”. Homer too, throughout his epic narration, also at the closing up of his scene of sports competition, never once omits offering sacrifices to gods.

The modern version of the lower part of this character 贝bèi are now both a character by itself and a radical that related to money or gold or the valuables. And it all comes from the image of a seashell: for at one time in history, the Chinese apparently used one sort of seashells as currency.

So the athletes compete 比赛 and get their seashells, I mean gold if they win.

And competition must lie in the heart of human nature: the little girl looks back at me, gives me a challenging look and says: 我们比赛,看谁跑得快(Wǒmen bǐsài, kàn shéi pǎo dé kuài)! And off she runs, racing away!

You must be logged in to post a comment.