—-How Chinese Characters were created? Part Two

It all started with drawing. But there is only so much you could draw. Pretty soon, the Chinese man realized that he has to come up with other ways to make characters.

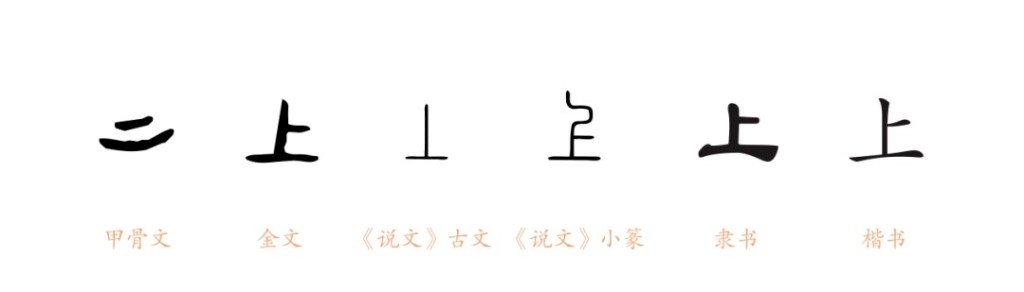

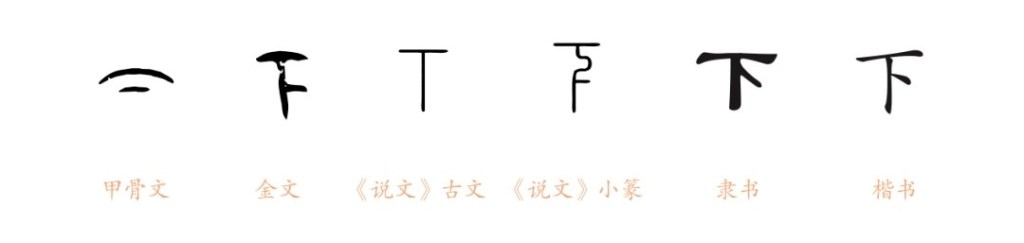

The first idea is easy enough: signs. Human knows how to use sign language long before they know how to speak, let alone to know the complicated system of written language. So when you point up it means up, and when you point down it means down.

But even with this brilliant idea, the Chinese man sees that there are still an awful amount of characters he needs to create.

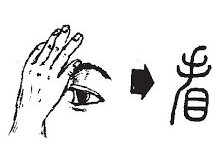

He thinks. He muses. He sighs. At last he sees before him, a man is putting a hand above his eyes, and even unconsciously, he looks at what that man is looking at, as if the man himself has told him “look!”

“Ah!” He thinks aloud. “I already have the character for ‘hand’ the character for ‘eyes’. If I put the hand above the eyes…..”

Do you still remember the symbol for “hand”?

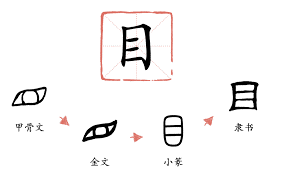

How about the drawing for “eyes”?

So what about putting a hand above your eyes?

So with this method, he managed to make many more characters:

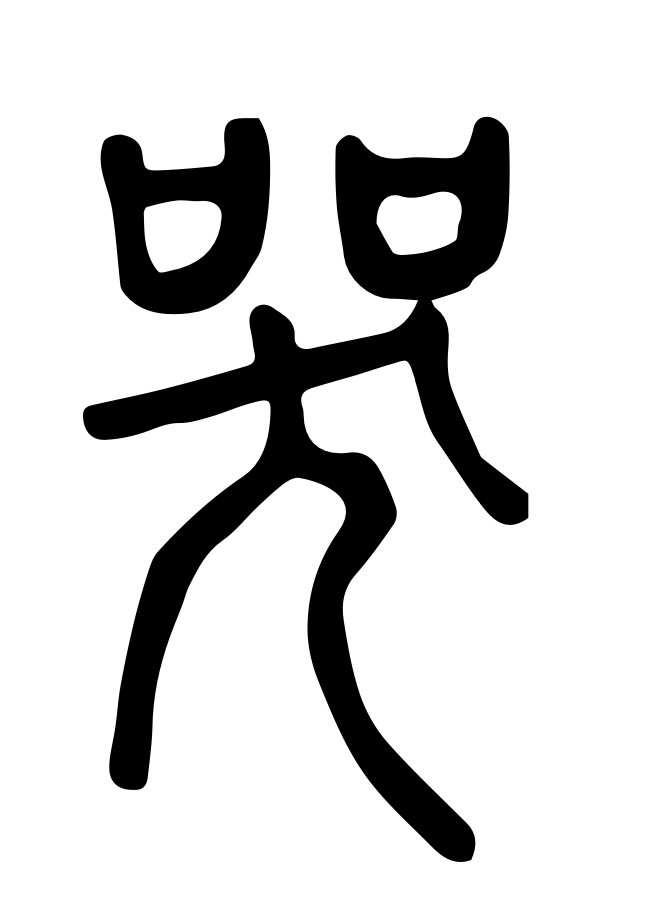

He sees one man at the heels of another man.

“That means ‘follow’.” he says to himself.

He sees the sun and he sees the full moon.

“One illuminates the day, the other the night. They are both bright.” He again muses to himself.

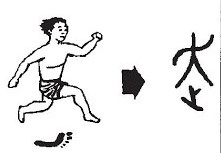

And a person waving his arms, with one foot on the ground, the other striding out means “walk”.

The close relationship between the Chinese and agriculture also shows in the characters, as words like “ox”, “goat” “pig” were the first created characters. So the concept that “the man begs food from the earth” was illustrated even in characters. As an inland country with a vast continent, the Chinese were not, roughly speaking, an ultra adventurous race: there was always land enough to plough and it never was worth one’s while to go to the sea and very likely get drowned. Even the word “water” is unlike the English word which shares the same root from “wave” of the sea. In Chinese the word “water”, instead of sea water, is from the river, and it flows with amazing tranquility and elegance.

You must be logged in to post a comment.