Three green benches in a row appeared into view, all unoccupied. I halted, gazed and considered. The early morning sun was still low behind some buildings, and all the three benches were in shade. I eventually chose the one on the side next to a cluster of bushes that promised the most privacy as much as an open space in a park could render. I then opened my book and presently was absorbed into another world.

Though the present world before long called me back. As I looked up from the pages, I saw that the sun now had risen high behind some tall trees, the spot I sat on was now in its white light, the heat had been accumulating, and now reached to an unpleasant degree. I accordingly moved, and in the course of the morning, I moved once and again from one bench to another as the sun moved and put now this bench in shade, now that.

The Chinese, from the very beginning, knows that time is about the movement of the sun. They put a sun 日rì in the character ‘time’ 时shí.

And it’s a pleasure to think that the Chinese tells time this way: they must have stood under the sky, gazed long and considered hard at the sun to be able to tell the precise time.

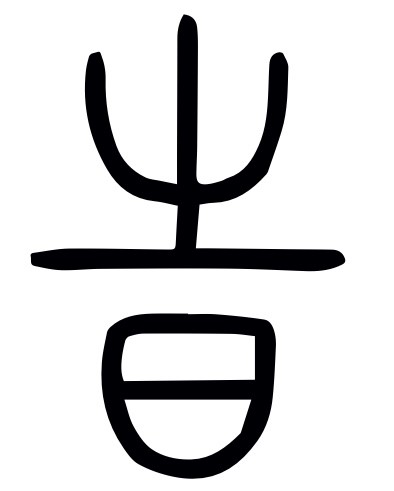

Indeed the character explains itself this way: 时shí, the left part is the sun 日 rì and the right part is a length unit 寸cùn.

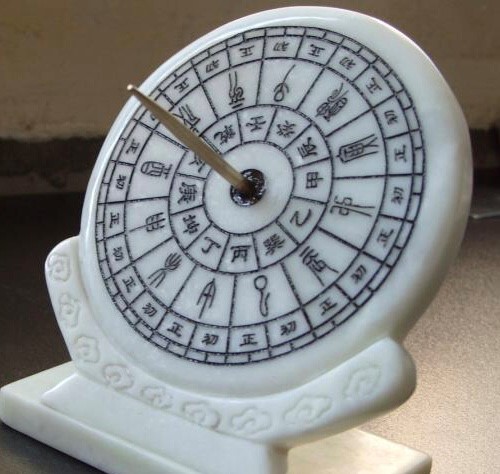

Of course they made a 日晷 rìguǐ after all the gazing and considering and calculating:

But the character 时 in its origin means not the time, the hour, the moment as it means now, but the four seasons ( Is this the reason that 时 sounds very similar to 四 sì four?). Though, despise the variation of meanings, the character from the start never deviated from the sun.

Later on ( though not much later, still far, far back from recent) the Chinese adds another character to mean time 间 jiān, and till today 时间 shíjiān still means ‘time’.

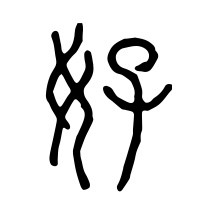

间 , as I look it up in the dictionary, proves to be a character that delights and worth much noticing: it all comes from a crack and the moon!

And this crack 间 went on becoming bigger and more important and now it means ‘time and space’.

Now the Chinese from the very beginning knows time is about the sun, about the movement of the sun: it moves a certain space in the sky and indicates a certain length of time. And not long after that–as astonishing as it sounds–they also figured out what Einstein would explain about two thousand years later in a more elaborated way that time is space, and that’s still how the Chinese interprets time today 时间, time and space are one (Yes. We certainly are an astonishingly smart race! Well, at times!)

So when the Westerners gaze at the sea to watch the tide–the English word ‘time’ comes from ‘tide’, the Chinese, being mostly inlanders, watches the sun moves across the sky, the four seasons come and go, the moonlight comes in through the crack, and says: “一寸光阴一寸金,寸金难买寸光阴 yī cùn guāng yīn yī cùn jīn, cùn jīn nán mǎi cùn guāng yīn“.

You must be logged in to post a comment.