—why you should learn Mandarin

It’s said you use more parts of your brain when you learn Chinese. It’s said it is the most beautiful language in the world. It now becomes more and more popular, and to have Chinese Program in schools in New York is no longer uncommon. And I encounter more and more youngsters who are undaunted by what is the “traditional way of thinking”: that it is a very difficult language, indeed the most difficult language; that it is impossible to learn it; that it sounds strange and looks puzzling.

They start to speak, they speak on. They learn the first character, they go on writing thousands more. They make mistakes. They stumble. They laugh and they get on with it. And in the end, to my great delight and to theirs, I listen to them speak like a Chinese. I watch them write like a Chinese. And thus one of the world’s most important cultures opens to them; thus the doors of 1.3 billion people open to them–that’s not even including Japanese and Korean where they still use Chinese characters. (Indeed in ancient Japan and Korea, only the most learned people, the high officials, had the privilege to study Mandarin Chinese.)

Say philosophy is in the language. Say the language is how we name the world, perceive the world, express ourselves and communicate with others. And there is awful a lot you could learn the mind, the culture of Chinese people by learning its tongue.

Take the most basic characters for examples.

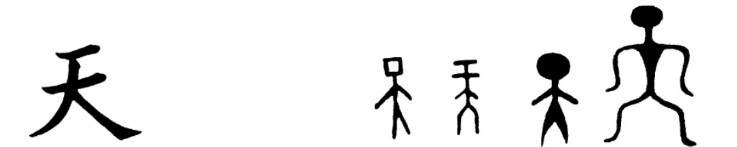

Take a moment to think. To think of humans. What is a human? If you have to draw–using the most economical way possible but at same time it has to convey your meaning–a symbol to mean human. What would you draw?

Would it be something like this?

Children often draw like this to mean a person, and Chinese too!

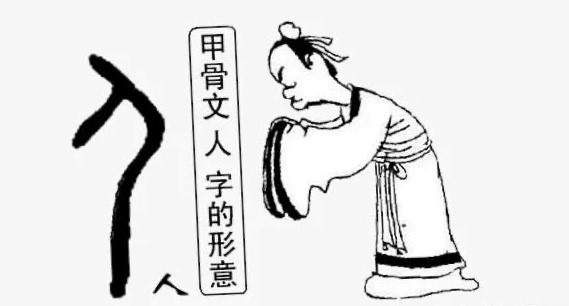

Here is how the Chinese character that means human came about:

And a very polite person indeed is he! (Guess where the custom of bowing in Japan comes from?)

And with time it evolves:

And now we use the last one to mean human which consists only two strokes.

So the courteous Chinese man looked into himself–human–and put down two strokes to mean a person. And in a way it also says the practicality of the Chinese!

—–more examples of Chinese Characters to be continued!

You must be logged in to post a comment.