At times, it’s no use to tell them to do this or to do that: they would just insist on imitating what you are doing. As I looked at the little girl on the screen and sent her a “clapping hands” for her effort, her eyes lit up and she at once asked me in an eager tone “how do you do that?”

She then said to me what I just said to her “我给你 Wǒ gěi nǐ….”(I give you……) and sent over what she chose to click.

“他在哭还是在笑? Tā zài kū háishì zài xiào?” (Is he crying or laughing?) I looked at it and asked her.

“Well, those are happy tears, he is laughing.” The little girl informed her slow-witted elder.

A piece of news I read later told me that this now re-popularized emoji was actually chosen by Oxford Dictionary in 2015 as the word of the year. “For the first time ever, Oxford Dictionary has chosen a ‘pictograph’ as its word of the year. They say the ‘face with tears of joy emoji’ best represents ‘the ethos, mood and preoccupation of the year’.

It’s said this emoji has been extremely popular in China. And unsurprisingly, there is actually a Chinese idiom to echo this ‘pictograph’: 哭笑不得 kūxiàobùdé literally ‘cry laugh not get’: not to know whether to cry or laugh, both funny and extremely embarrassing, between laughter and tears.

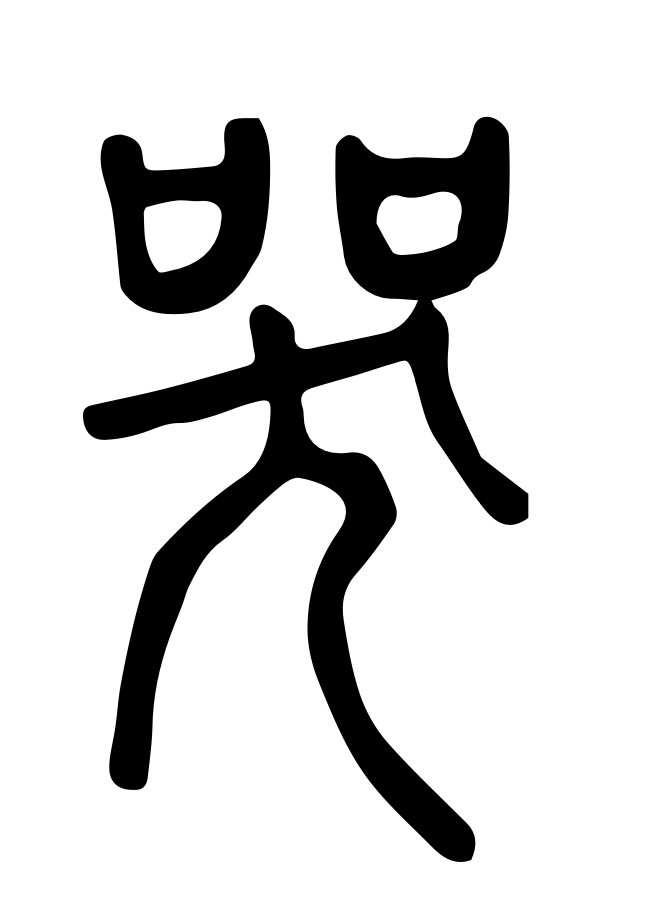

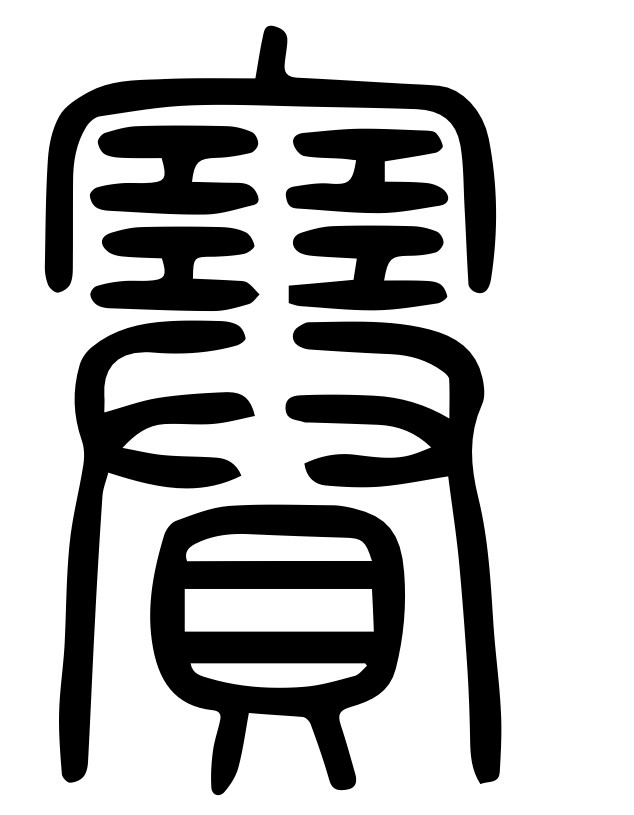

哭kū, to cry, at first sight it’s easy to mistake those two squares on the top for eyes and the dot below for the tear. Though the origin of this word comes not from the image of tears but from the sound of howling, the squares are not eyes but a wailing mouth:

The explanation of this character might, perhaps, remind you of a howling child you would occasionally see: they do bawl out in so loud and bitter a tone, waving their hands and stomping their feet in front of an–sometimes embarrassed, sometimes nonchalant–adult. And I often cannot help but look up amazed: what bitterness must inspire that hearty wailing? (Often, no doubt, it is small things like: he needs to go home to take his nap……)

At creating this character, the Chinese might have looked at the howling child, or he might have looked at an adult who is crying out his real woes:

For the little girl–children, if you allowed them, have amazing ability to make up stories–it is happy tears, and who is to say it is not? And may we all in our long lives have more tears like those.

But what about yourself? What is a 哭笑不得 situation for you?

You must be logged in to post a comment.