We were learning animal names, and the little boy, eagerly pressing down the dog button, said “woof, woof, woof.”

It, admittedly, was not the first time I learned animals with small children, and nor it was the first time I heard “woof” from the small mouth of a prattling child. Still, it brings a smile to my face every time I hear it.

I remember, in wonder when first arrived in northern Europe, Sweden, I listened to their strange talk, for me it sounded somehow like knocks on the wood, and it suited, in my mind, the cool, crisp northern air came in to my nose and the clear, blue northern sky that came in to my eye. And when they in groups, and with much vigor, roaring out “Ya! Ya! Ya!”, they seemed to me so many vikings fresh out of their boat.

The locality, the enviroment we live in must have such profound influences on our tongues that the mountains, the oceans and the air seem to shape the voice we utter to fit in its landscape.

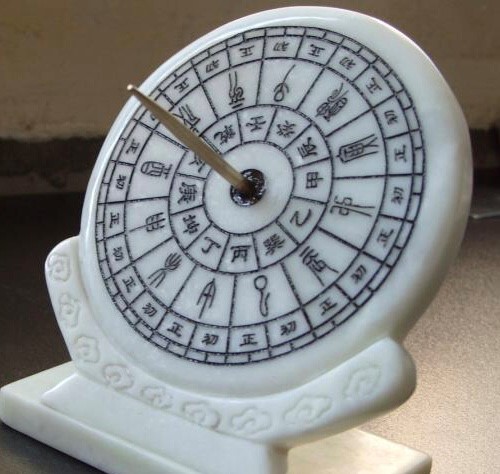

China boasts a vast territory and a wide geographical span (地大物博dìdàwùbó). It covers almost all terrains, from high towering moutains to deep flowing rivers. And, perhaps in an effort to echo this variety, tones are developed in its language, the bright sound and sonorous intonations go up and down, full of changes. The syllables, well-defined and limited, are normally short and clear, and it’s said these phonetics characteristics make the language sound melodious and full of music.

The dog, be it comes from China or America, of course, says the same thing, it’s only we interpret it differently.

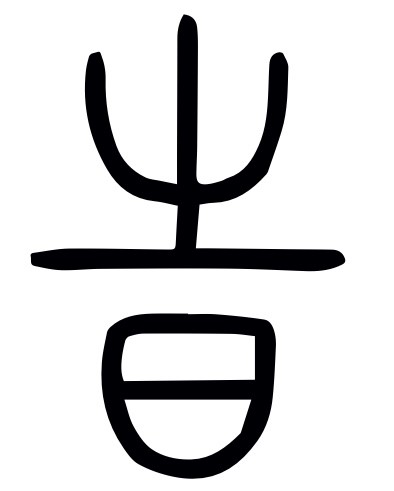

So while the American says their dogs bark “woof”, the Chinese hears theirs howl out a clear and short: “Wang! Wang! Wang!” (狗gǒu,汪!汪!汪!)

And they hear the cat calls out “Miao! Miao! Miao!” (猫māo,喵!喵!喵!)

Duck goes “Ga! Ga! Ga! ( 鸭yā,嘎!嘎!嘎!)

Bird goes “Ji! Ji! Ji!” (鸟niǎo, 叽!叽!叽!)

……

“The names we give animal sounds are not straight-up imitations of those sounds. They are interpretations of those sounds, filtered through phonemes of a given language.” So the internet tells me.

Each language’s interpretation may be different, there is, however, something in common, we being human, and being naturally anthropocentric, think the animals say the language we choose to speak and hear, and think also, with much arrogance, that we could stand apart and impose on Nature without seeing that we are in it, we are part of it, and the influences and the communications are in both ways.

You must be logged in to post a comment.